What is Equal Area Criterion?

What is Equal Area Criterion?

Equal Area Criterion Definition

The equal area criterion is a graphical method to determine the transient stability of a single or two-machine system against an infinite bus.

Equal Area Criterion for Stability

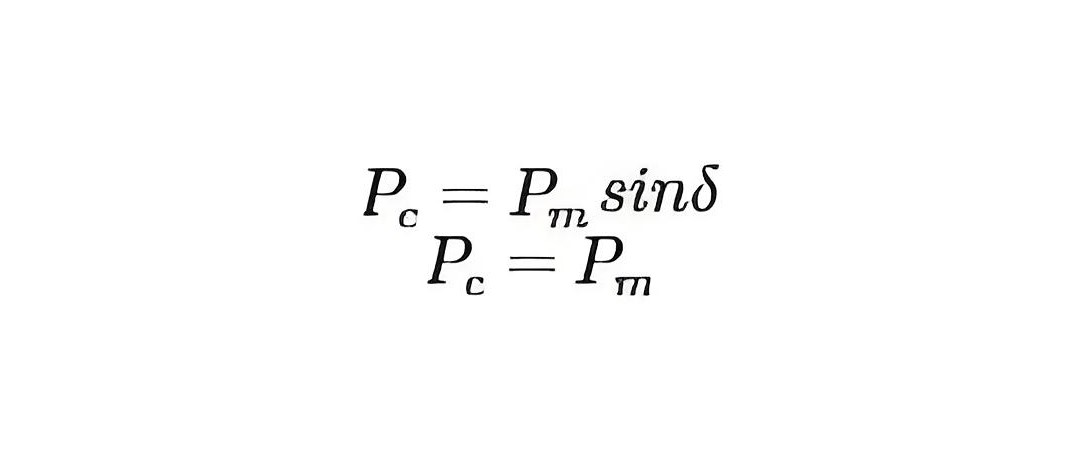

Over a lossless line, the real power transmitted will be Consider a fault occurs in a synchronous machine which was operating in steady state. Here, the power delivered is given by

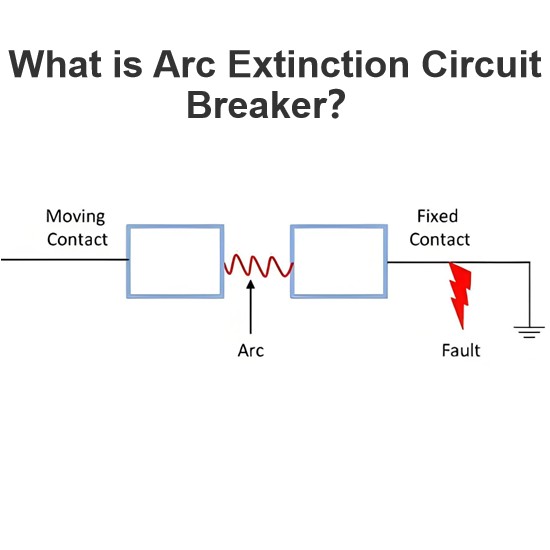

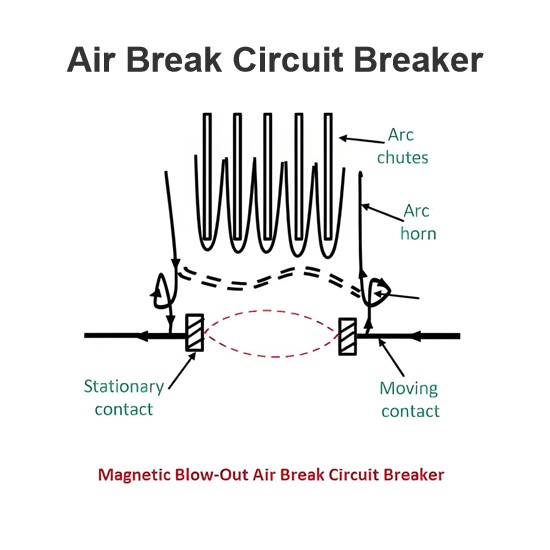

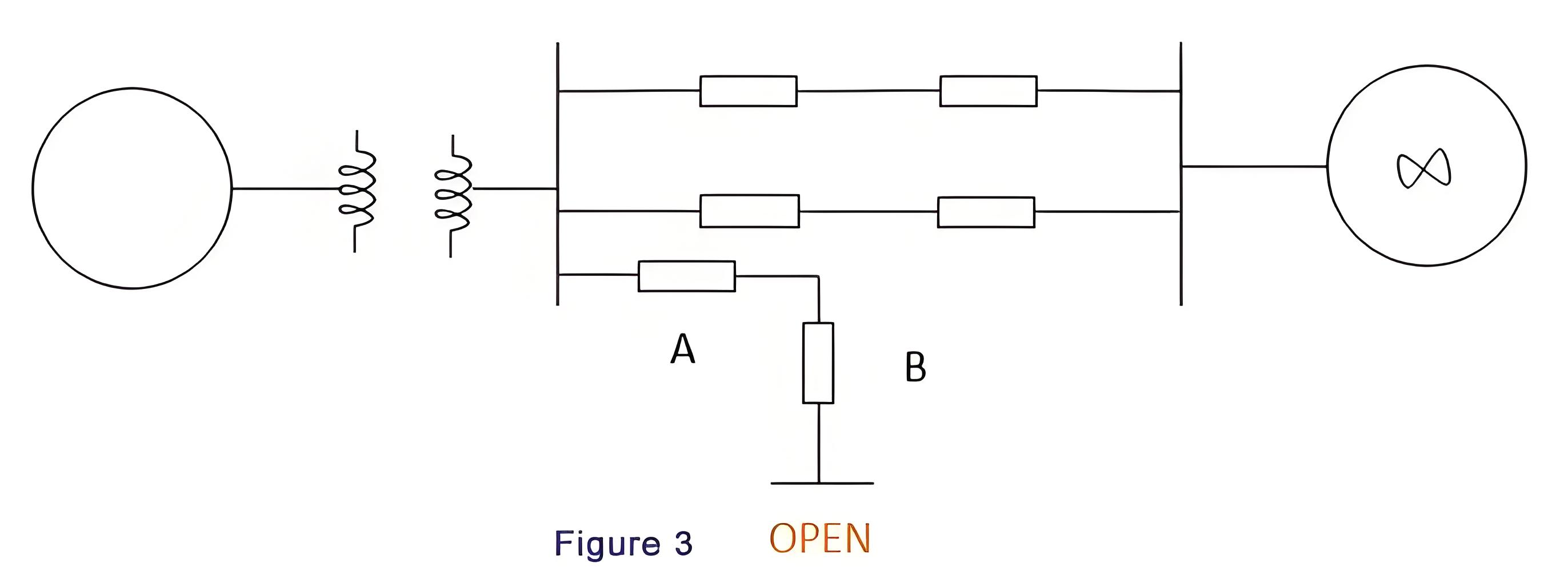

To clear a fault, the circuit breaker in the affected section must open. This takes about 5 to 6 cycles, and the following post-fault transient lasts a few more cycles.

The prime mover, driven by a steam turbine, provides input power. The time constant for a turbine mass system is a few seconds, while for the electrical system, it’s milliseconds. Therefore, during electrical transients, mechanical power remains stable. Transient studies focus on the power system‘s ability to recover from faults and provide stable power with a new load angle (δ).

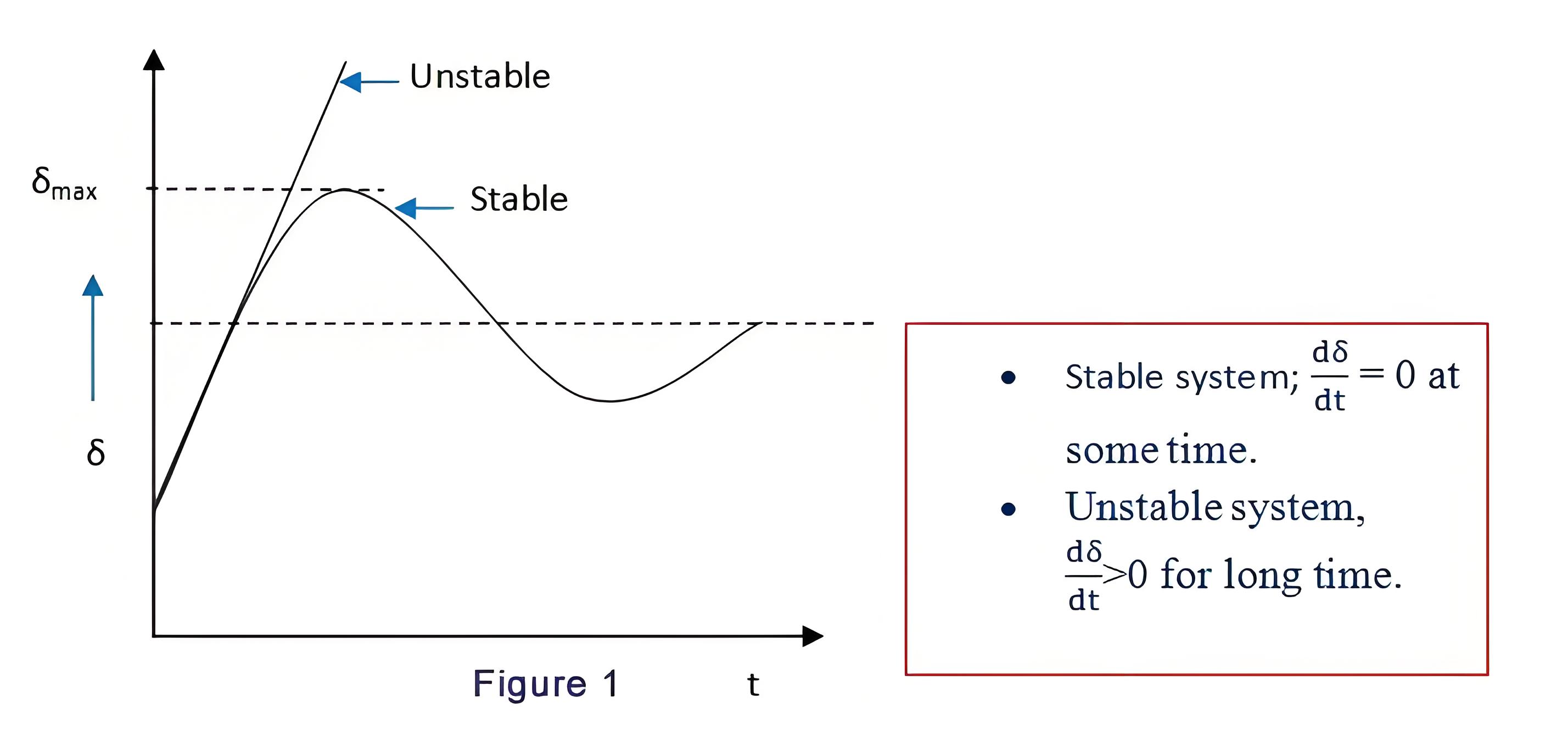

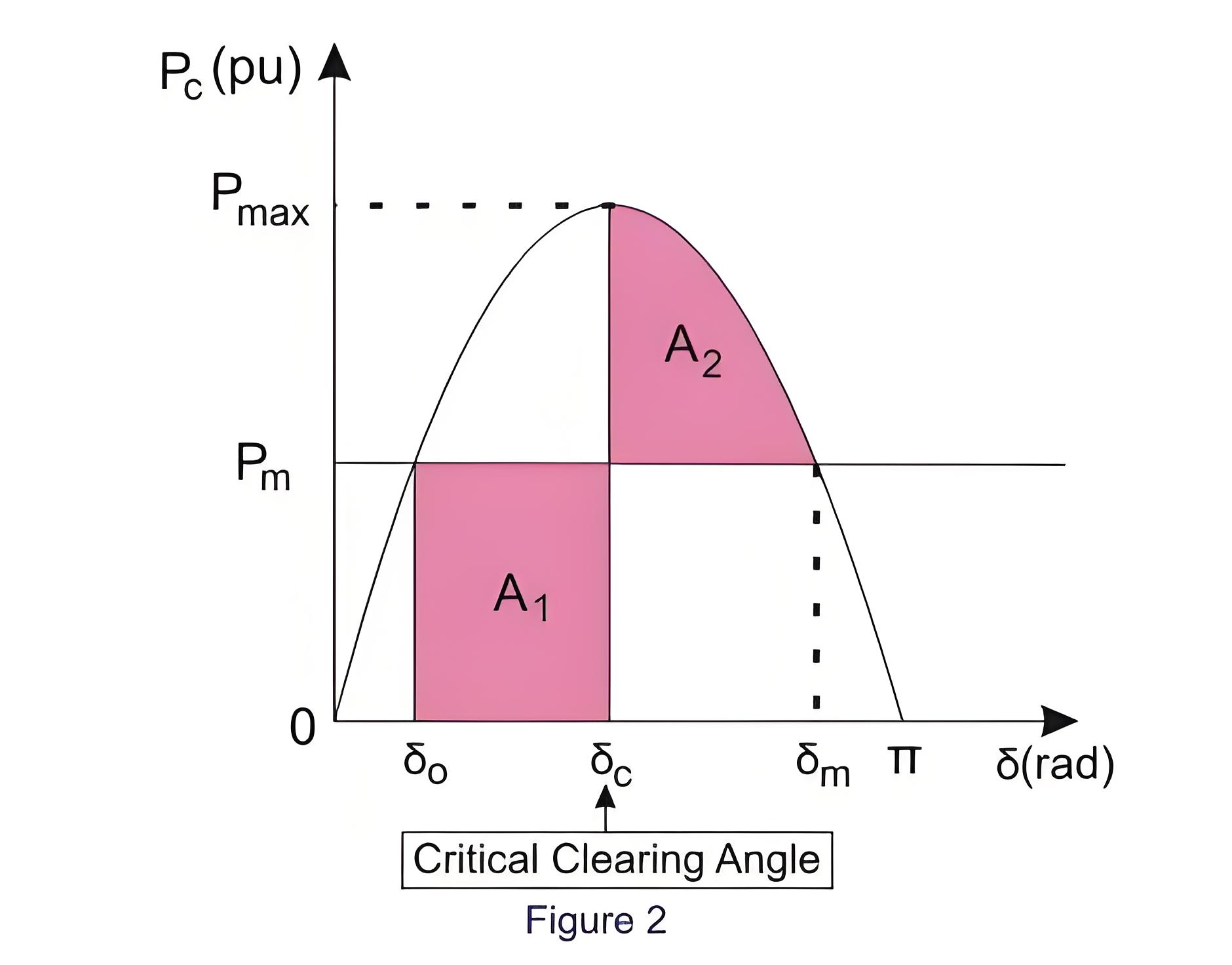

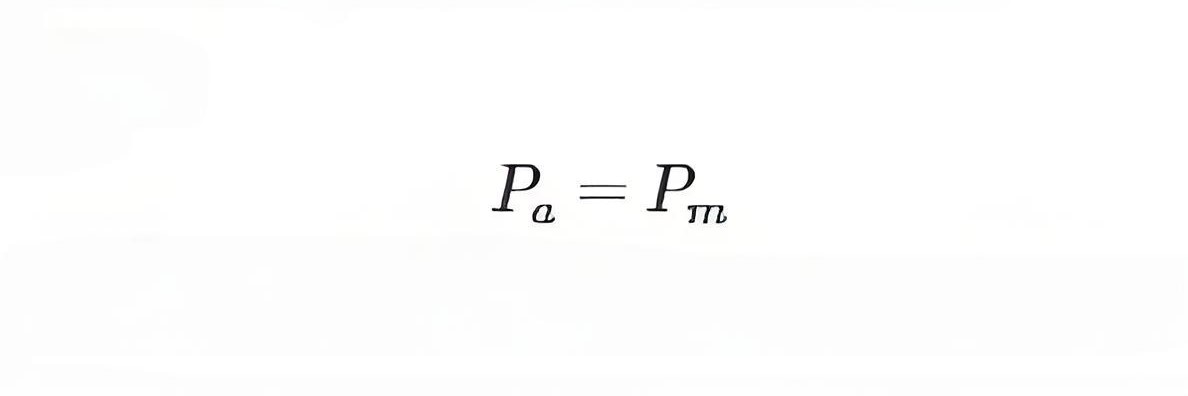

The power angle curve is considered which is shown in fig.1. Imagine a system delivering ‘Pm’ power on an angle of δ0 (fig.2) is working in a steady state. When a fault occurs; the circuit breakers opened and the real power is decreased to zero. But the Pm will be stable. As a result, accelerating power.

The power differences will result in rate of change of kinetic energy stored within the rotor masses. Therefore, due to the stable influence of non-zero accelerating power, the rotor will accelerate. Consequently, the load angle (δ) will increase.

Now, we can consider an angle δc at which the circuit breaker re-closes. The power will then come back to the usual operating curve. At this moment, the electrical power will be higher than the mechanical power. But, the accelerating power (Pa) will be negative. Therefore, the machine will get decelerate. The load power angle will still continue to increase because of the inertia in the rotor masses. This increase in load power angle will stop in due course and rotor of the machine will start to decelerate or else the synchronisation of the system will get lose.

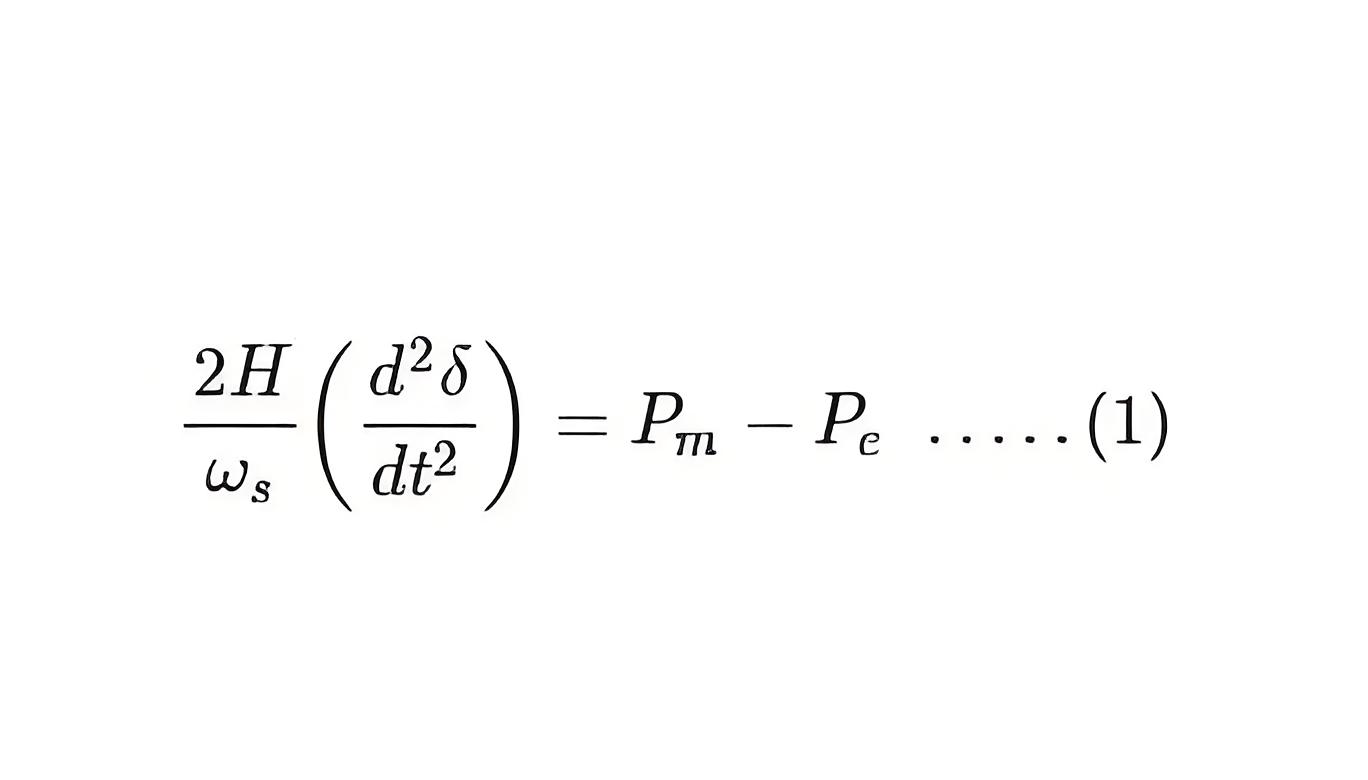

The Swings equation is given by

Pm → Mechanical power

Pe → Electrical power

δ → Load angle

H → Inertia constant

ωs → Synchronous speed

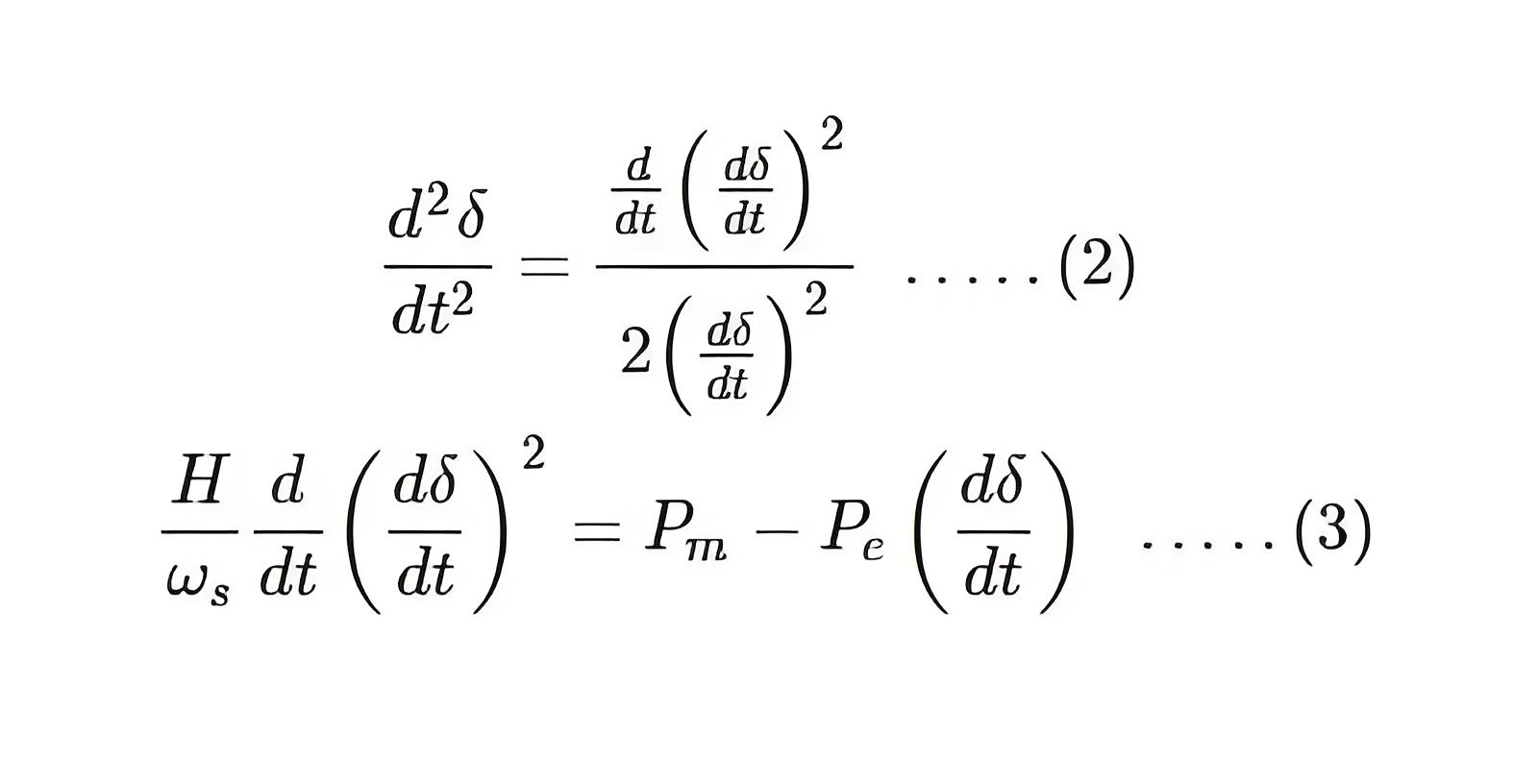

We know that,

Putting equation (2) in equation (1), we get

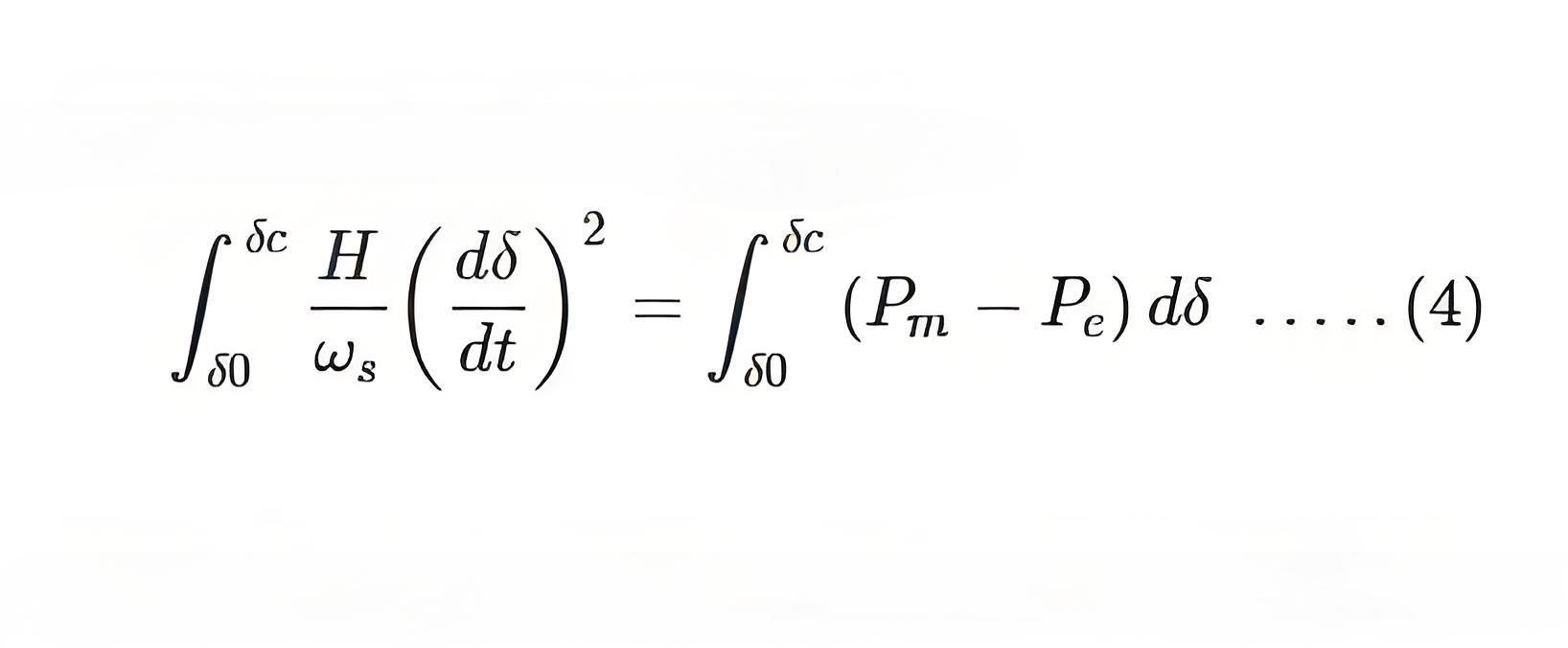

Now, multiply dt to either side of equation (3) and integrate it among the two arbitrary load angles which are δ0 and δc. Then we get,

Assume the generator is at rest when load angle is δ0. We know that

At the time of occurrence of a fault, the machine will start to accelerate. When the fault is cleared, it will continue to increase speed before it reaches to its peak value (δc). At this point,

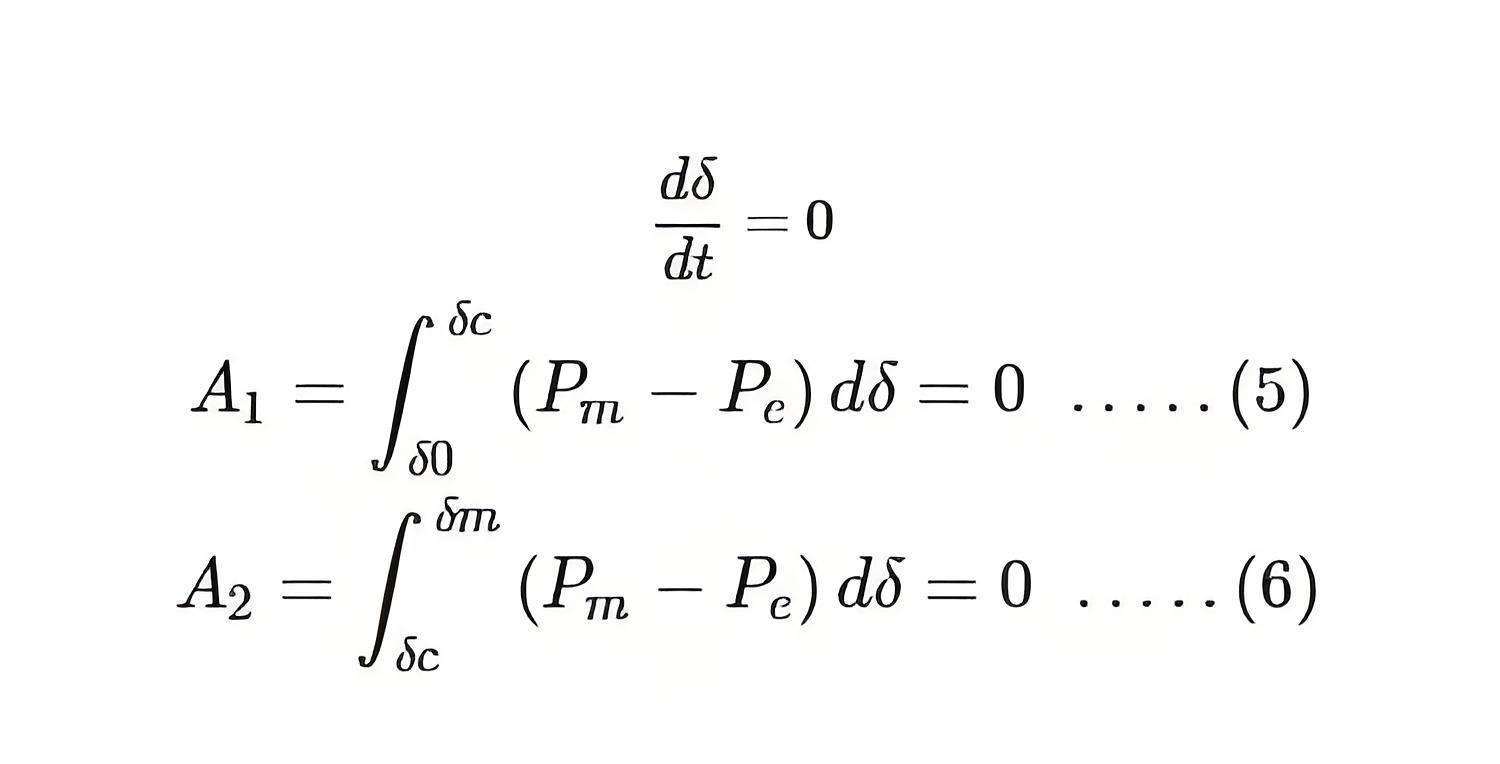

So the area of accelerating from equation (4) is

Similarly, the area of deceleration is

Next, we can assume the line to be reclosed at load angle, δc. In this case, the area of acceleration is bigger than area of deceleration.

A1 > A2. The load angle of the generator will pass the point δm. Beyond this point, the mechanical power is greater than electrical power and it forces the accelerating power to remain positive. Before slowing down, the generator therefore gets accelerate. Consequently, the system will become unstable.

When A2 > A1, the system will decelerate entirely before getting accelerated again. Here, the rotor inertia will force the successive acceleration and deceleration areas to become smaller than the previous ones. Consequently, the system will reach steady state.

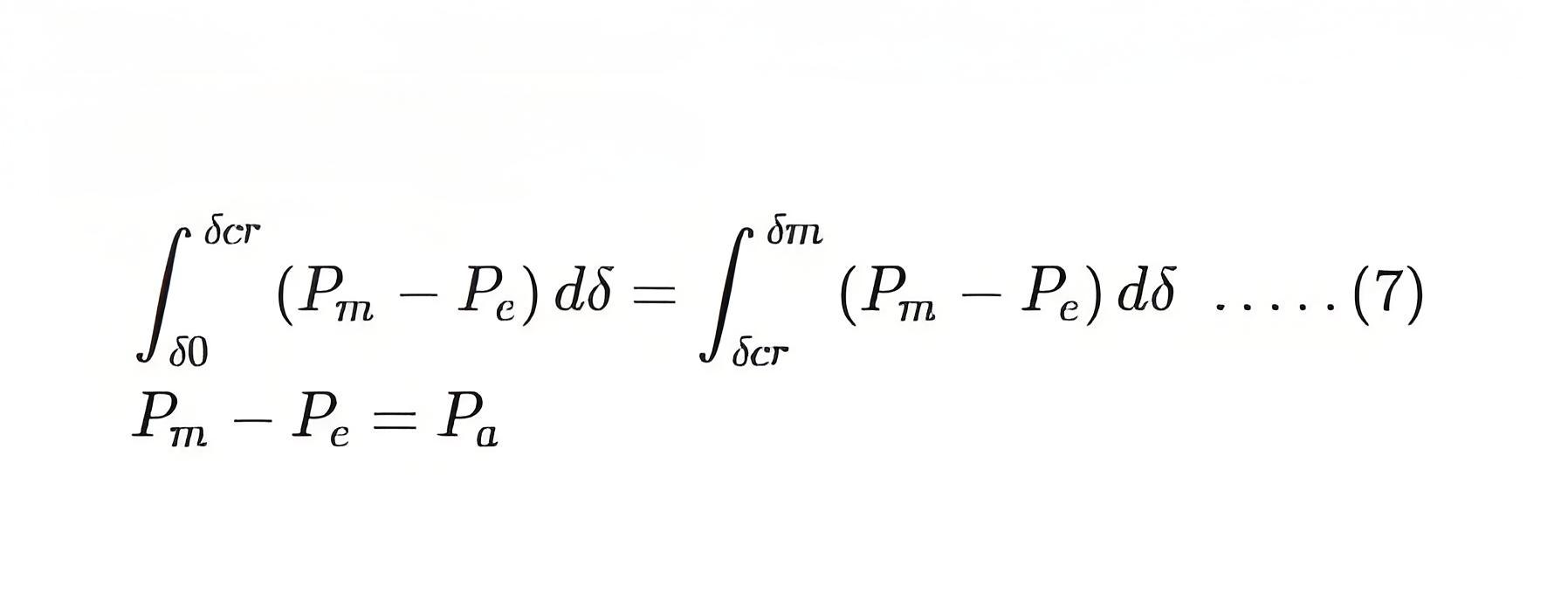

When A2 = A1, the margin of the stability limit is defined by this condition. Here, the clearing angle is given by δcr, the critical clearing angle.

Since, A2 = A1. We get

The critical clearing angle is related to the equality of areas, it is termed as equal area criterion. It can be used to find out the utmost limit on the load which the system can acquire without crossing the stability limit.

c

c

The Electricity Encyclopedia is dedicated to accelerating the dissemination and application of electricity knowledge and adding impetus to the development and innovation of the electricity industry.