Key Concepts of Magnetic Materials

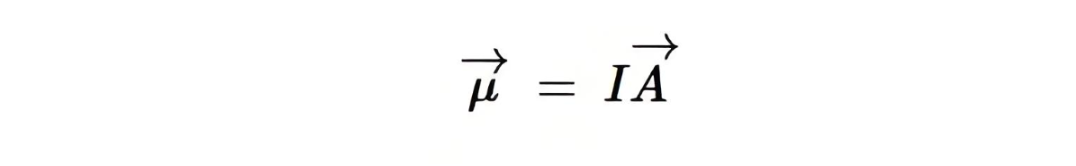

The Magnetic Dipole Moment

When exposed to the same external magnetic field, different materials can exhibit vastly different responses. To delve into the underlying reasons, we must first grasp how magnetic dipoles govern magnetic behavior. This understanding begins with an exploration of the magnetic dipole moment.

The magnetic dipole moment, often referred to as the magnetic moment for simplicity, serves as a fundamental concept in electromagnetics. It offers a powerful tool for comprehending and quantifying the interaction between a current - carrying loop and a uniform magnetic field. The magnetic moment of a current loop, which has an area A and carries a current I, is defined as follows:

Note that the area is defined as a vector, which makes the magnetic moment a vector quantity as well. Both vectors have the same direction.

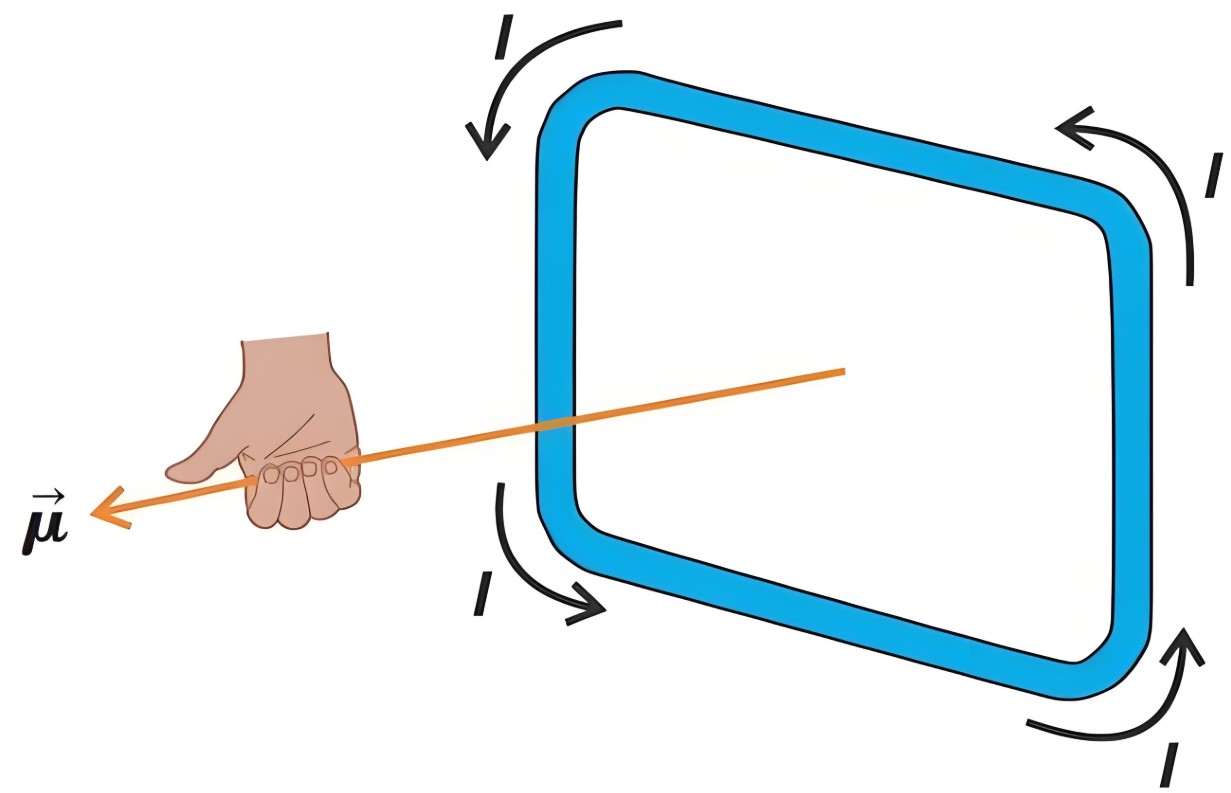

The direction of the magnetic moment is perpendicular to the plane of the loop. It can be found by applying the right-hand rule—If you curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the current flow, your thumb shows the direction of the magnetic moment vector. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

The magnetic moment of a loop is solely determined by the current flowing through it and the area it encloses. It remains unaffected by the loop's shape.

Torque and the Magnetic Moment

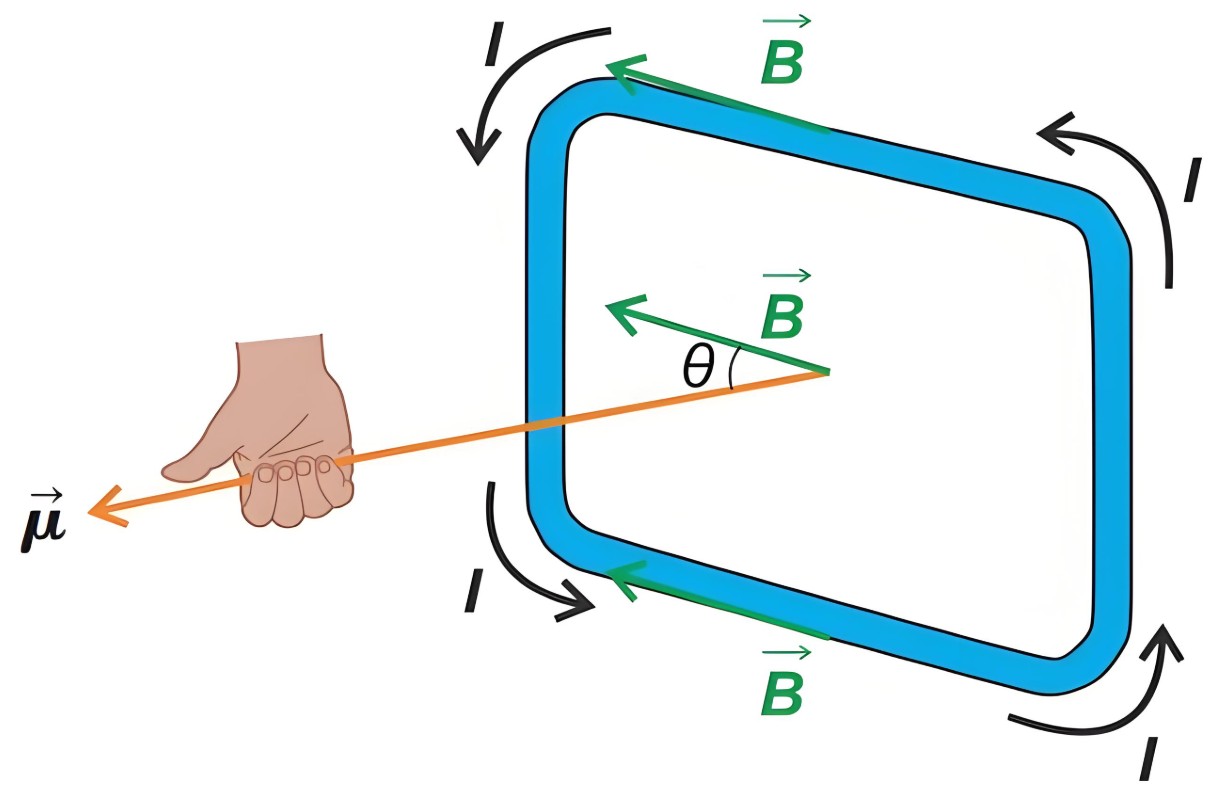

Take a look at Figure 2, which depicts a current - carrying loop positioned within a uniform magnetic field.

In the figure presented above:

I represents the current.

B denotes the magnetic field vector.

u stands for the magnetic moment.

θ indicates the angle between the magnetic moment vector and the magnetic field vector.

Since the forces acting on the opposite sides of the loop counterbalance each other, the net force acting on the loop sums up to zero. Nevertheless, the loop is subject to a magnetic torque. The magnitude of this torque exerted on the loop is given as follows:

From Equation 2, we can clearly observe that the torqu (t)is directly correlated with the magnetic moment. This is because the magnetic moment acts like a magnet; when placed in an external magnetic field, it experiences a torque. This torque always has a tendency to rotate the loop towards the stable equilibrium position.

Stable equilibrium is achieved when the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of the loop (i.e.,θ=0^o ). If the loop is slightly rotated away from this position, the torque will act to restore the loop back to the equilibrium state. The torque is also zero when θ=180^o . However, in this case, the loop is in an unstable equilibrium. A minor rotation from θ=180^o will cause the torque to drive the loop further away from this point and towards θ=0^o .

Why is the Magnetic Moment Important?

Numerous devices depend on the interaction between a current loop and a magnetic field. For instance, the torque generated by an electric motor is based on the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and the current - carrying conductors. During this interaction, the potential energy varies as the conductors rotate.

It is the interaction between the magnetic moment and the external magnetic field that gives rise to potential energy in our magnetic system. The angle between these two vectors determines the amount of energy (U) stored in the system, as shown in the following equation:

The following presents the stored energy values for several crucial configurations:

When θ=0^o , the system is in a stable equilibrium state, and the stored energy reaches its minimum, with U=-uB.

When θ=90^o , the stored energy has risen to U=0 .

When θ=180^o, the stored energy attains its maximum value, U=uB . This particular state represents the unstable equilibrium position.

Understanding the Net Magnetic Moment via the Atomic Model

To comprehensively grasp how magnetic materials generate a magnetic field, delving into quantum mechanics is essential. However, since that topic lies beyond the scope of this article, we can still leverage the concept of the magnetic moment and the classical atomic model to gain valuable insights into how materials interact with an external magnetic field.

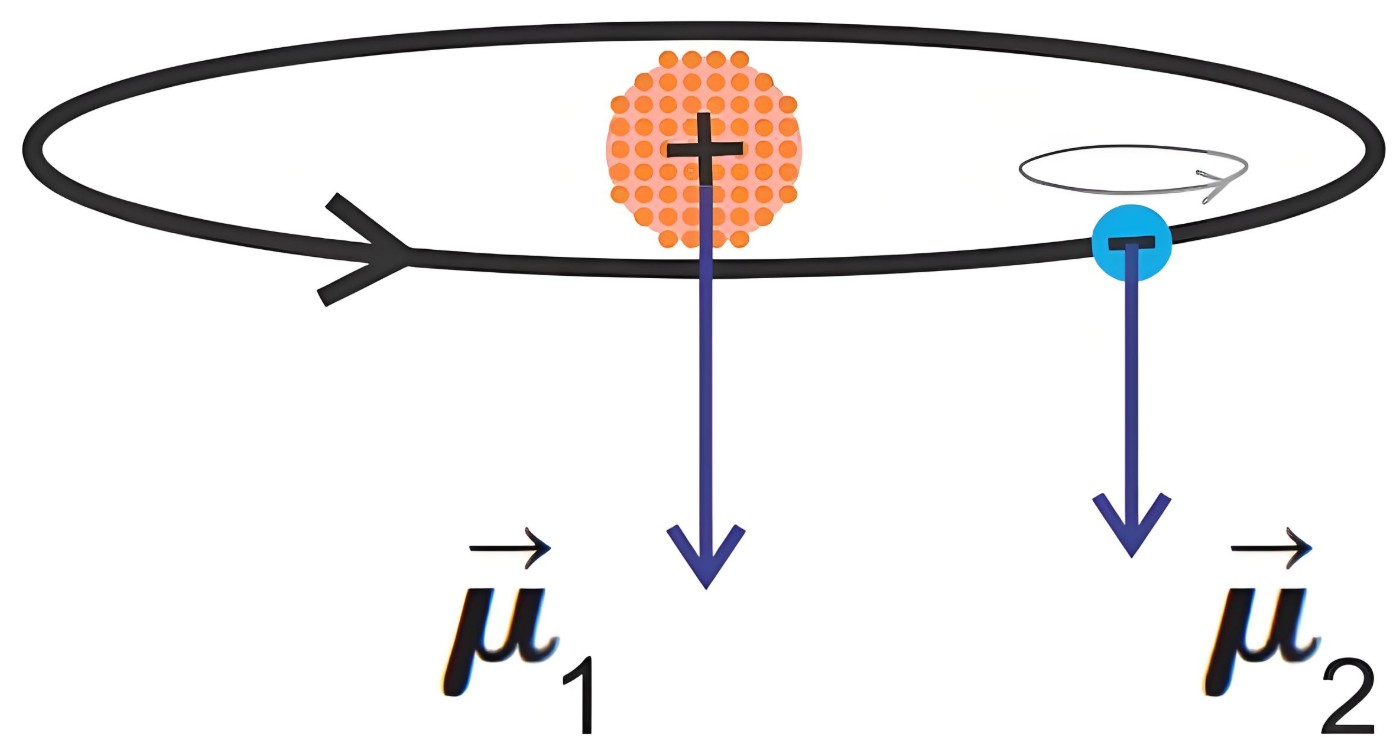

This model depicts an electron as both orbiting the atomic nucleus and spinning around its own axis, as vividly shown in Figure 3.

The Net Magnetic Moment of Electrons, Atoms, and Objects

The orbital motion of an electron can be likened to a tiny current - carrying loop. As a result, it generates a magnetic moment (denoted as (u1 )in the figure above). Similarly, the electron's spin also gives rise to a magnetic moment (u2). The net magnetic moment of an electron is the vector sum of these two magnetic moments.

For an atom, its net magnetic moment is the vector sum of the magnetic moments of all its electrons. Although protons in an atom also possess a magnetic dipole, their overall effect is typically negligible when compared to that of electrons.

The net magnetic moment of an object is determined by taking the vector sum of the magnetic moments of all the atoms within it.

The Magnetization Vector

The magnetic properties of a material are determined by the magnetic moments of its constituent particles. As previously discussed in this article, these magnetic moments can be thought of as tiny magnets. When a material is placed in an external magnetic field, the atomic magnetic moments within the material interact with the applied field and experience a torque. This torque has a tendency to align the magnetic moments in the same direction.

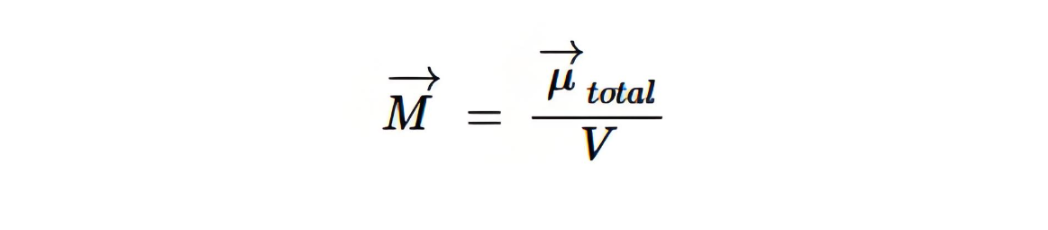

The magnetic state of a substance hinges on two factors: the number of atomic magnetic moments present in the material and the degree of their alignment. If the magnetic moments generated by microscopic current loops are randomly oriented, they will tend to cancel each other out, resulting in a negligible net magnetic field. To describe the magnetic state of the substance, we introduce the magnetization vector. It is defined as the total magnetic moment per unit volume of the substance:

where V represents the volume of the material.

When the material is exposed to an external magnetic field, its magnetic moments tend to align, leading to an increase in the magnitude of the magnetization vector. The characteristics of the magnetization vector are also influenced by the material's classification as paramagnetic, ferromagnetic, or diamagnetic.

Paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials consist of atoms with permanent magnetic moments. In contrast, the atomic magnetic moments in diamagnetic materials are not permanent.

Finding the Total Magnetic Field: Permeability and Susceptibility

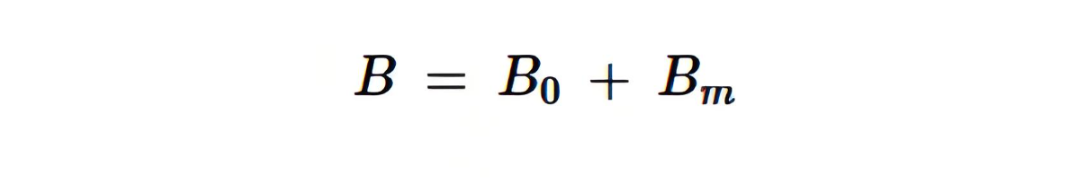

Suppose we place a material within a magnetic field. The total magnetic field inside the material has two distinct sources:

The externally applied magnetic field (B0).

The magnetization of the material in response to the external field (Bm).

The total magnetic field inside the material is the sum of these two components:

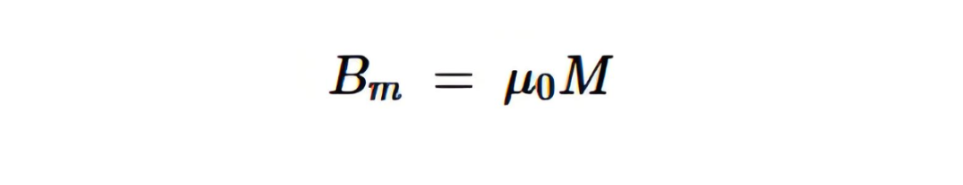

B0 is produced by a current-carrying conductor; Bm is produced by the magnetic substance. It can be shown that Bm is proportional to the magnetization vector:

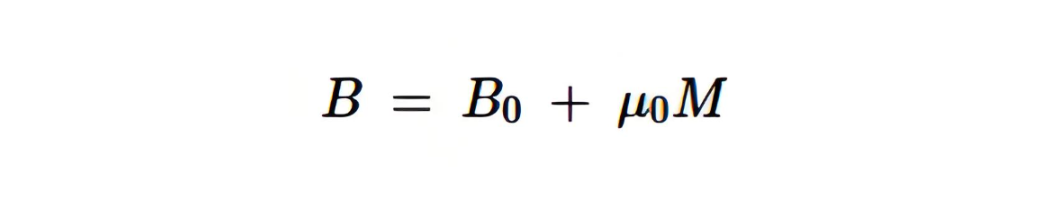

where μ0 is a constant called permeability of free space. Therefore, we have:

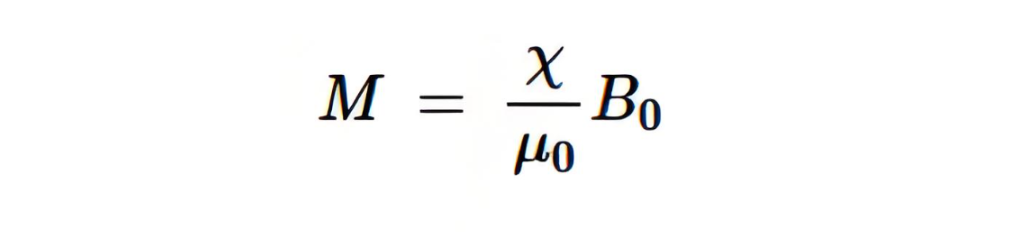

The magnetization vector is also related to external field by the following equation:

where the Greek letter χ is a proportionality factor known as magnetic susceptibility. The value of χ depends on the type of material.

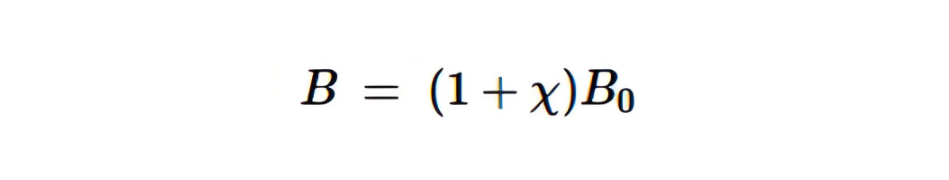

Combining the last two equations, we have:

The Significance of the Equation and Relative Permeability

This equation has an intuitive interpretation: it indicates that the total magnetic field inside the material is equivalent to the externally applied magnetic field multiplied by the factor 1+x . This factor, referred to as the relative permeability, serves as a crucial parameter for characterizing how a material responds to a magnetic field. The relative permeability is commonly denoted by ur.

Magnetic Susceptibility of Different Materials

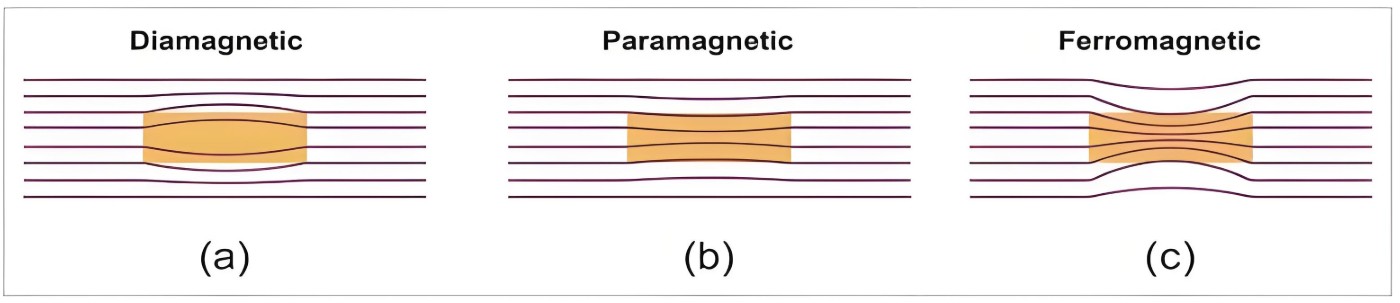

Figure 4 depicts the magnetic behavior of three distinct types of materials when they are placed in a uniform magnetic field. The interior area of the material is represented by a yellow rectangle.

Magnetic Susceptibility of Different Materials

In Figure 4(a), the magnetic field lines inside the material are more widely spaced compared to those outside. This indicates that the total magnetic field inside a diamagnetic material is slightly weaker than the externally applied field. For diamagnetic materials, the magnetic susceptibility (X) is a small negative value. For instance, at 300 K, copper has a magnetic susceptibility of –9.8 × 10⁻⁶. As a result, the material partially repels the magnetic field from its interior.

Figure 4(b) demonstrates the response of a paramagnetic material. Here, the magnetic field lines inside the material are more closely packed than those of the external field. This implies that the total magnetic field inside the material is slightly stronger than the external field. For paramagnetic materials, X is a small positive value. For example, at 300 K, the magnetic susceptibility of lithium is 2.1 × 10⁻⁵.

Finally, in Figure 4(c), the ferromagnetic material distorts the magnetic field lines, causing them to pass through the material. The material becomes magnetized, significantly boosting the magnetic field inside. For ferromagnetic materials, X has a positive value ranging from 1,000 to 100,000. Due to their high magnetic susceptibility, these materials generate a magnetic field that is much stronger than the externally applied one.

It's important to note that for ferromagnetic materials, is not a constant. Consequently, the magnetization (M) is not a linear function of the externally applied magnetic field (B0).

Wrapping Up

Magnetic materials are crucial in a wide variety of applications, including transformers, motors, and data storage devices. The magnetic state of a substance depends on the number of atomic magnetic moments in the material and how well they align in the presence of an external magnetic field. As briefly discussed, we can classify magnetic materials into three types based on these criteria: paramagnetic, diamagnetic, and ferromagnetic. We will explore these categories in more detail in a future article.

The Electricity Encyclopedia is dedicated to accelerating the dissemination and application of electricity knowledge and adding impetus to the development and innovation of the electricity industry.